Although the 36-page pamphlet is primarily devoted to landscape architecture, it makes some reference to “Prairie style” architecture. For instance, the publication highlights a couple of residences designed by William Drummond, an architect who began his career in Louis Sullivan’s office and worked on and off for Frank Lloyd Wright before establishing his own practice in 1908. As a photo caption reveals, Drummond stated that he “purposely repeated the prairie line in the roofs” of his home designs.

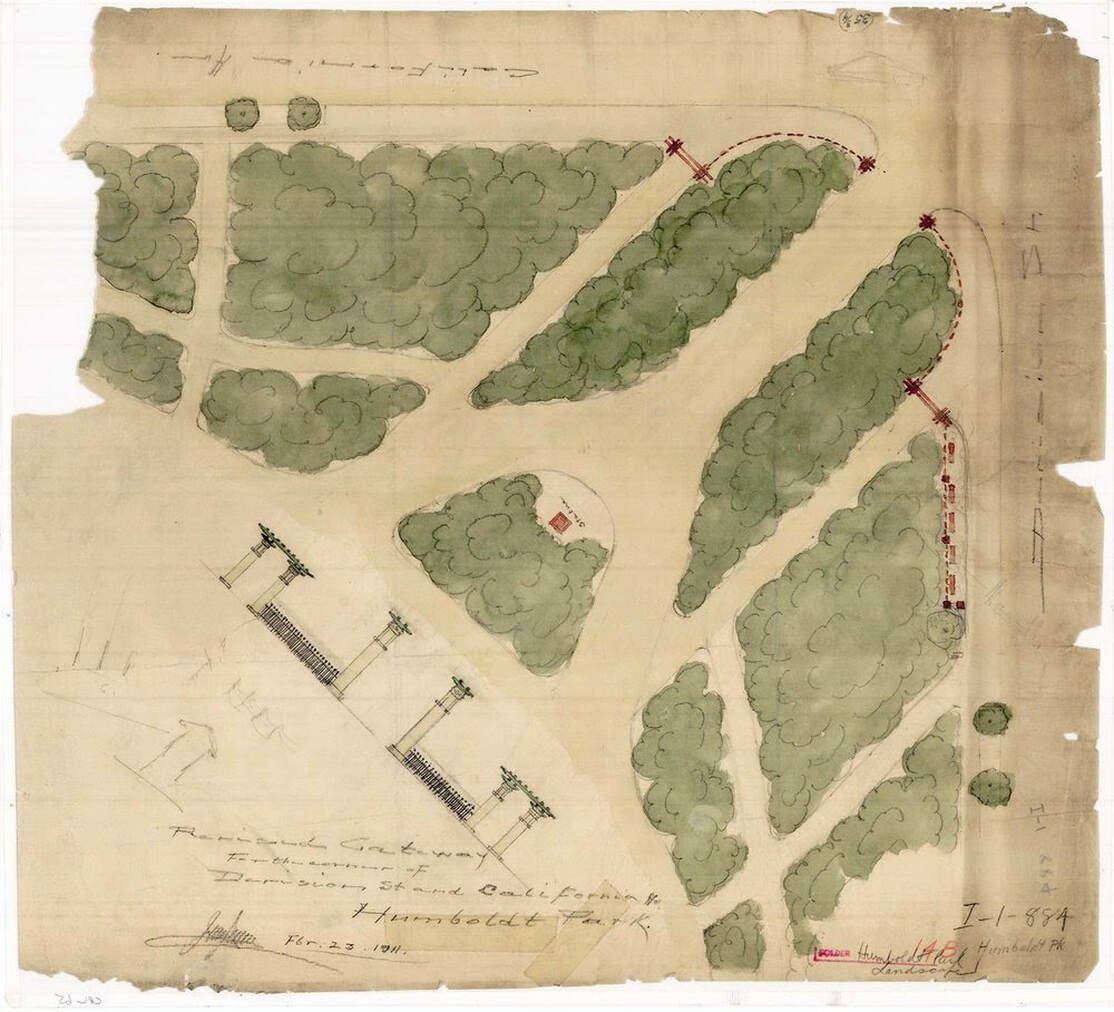

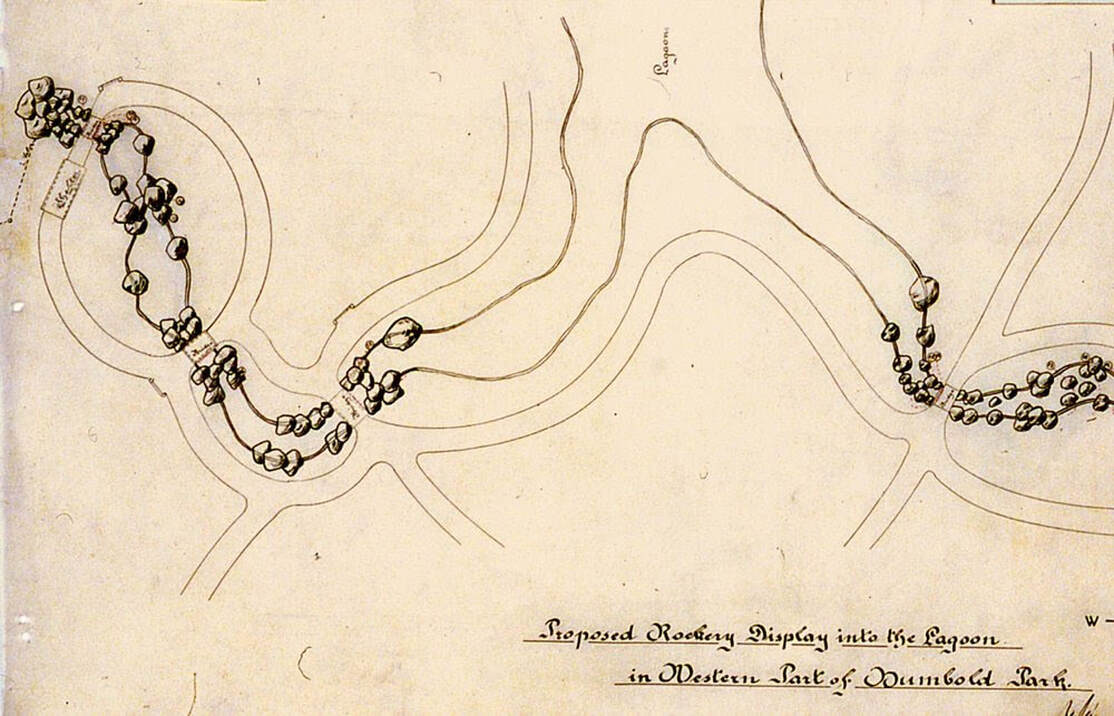

Jens Jensen, who had begun working as street sweeper in the 1880s, was appointed Superintendent of the entire West Park System in 1905. A Danish immigrant, Jensen saw great beauty in the area’s natural landscapes, at a time when many Chicagoans considered them to be flat, monotonous sites with little scenic value. Jensen, Simonds, and other kindred spirits, including architect Dwight Heald Perkins, formed a group called the Saturday Afternoon Walking Club that went on hikes through natural areas and advocated for their conservation. Soon after his appointment as the parks’ chief, Jensen directed approximately $4,000,000 n improvements to Humboldt, Garfield, and Douglas Parks. Jensen explained: “…of course, the primary motive was to give recreation and pleasure to the people, but the secondary motive was to inspire them with the vanishing beauty of the prairie.” Miller’s bulletin suggested that Prairie style landscapes were not all based on the “literal restoration” of natural scenery. Some examples – especially those in urban parks “that were visited by thousands of people daily” – could be described as “conventionalized” prairie landscapes. By “conventionalized,” Miller refers to spaces that included formal elements and straight lines. For instance, at Humboldt Park, Jensen created a corner gateway that provided a transition from the busy city street into his naturalistic landscape within the park.

Jensen severed his ties with Chicago’s parks in 1921, but his influence didn’t end at that time. Alfred Caldwell (1903-1998), Jensen’s disciple, worked for the Chicago Park District for several years in the 1930s. Working on projects that were funded by the federal Works Progress Administration, Caldwell was extremely productive. His “Prairie style” legacy remains at Riis Park and at Burnham Park’s Promontory Point, which was recently listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Most extraordinary of all is the Alfred Caldwell Lily Pool in Lincoln Park—also a designated National Historic Landmark. This composition of native plants, Prairie River, limestone paths and ledges, council ring, Japanese-inspired gate, and Prairie style shelter pays homage to Jensen, but with Caldwell’s own artful stamp. I hope this overview has whetted your appetite and that you’ll consider participating in my Prairie in the Parks seminar! You can sign up for individual sessions, or the whole series.

To subscribe to Julia Bachrach's informative newsletter or see more of her articles, check out her website at https://www.jbachrach.com/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

AuthorDebra Hammond is currently an officer of Promontory Point Conservancy. She has always been tall for her age |